By Leo Carnevale

Translated by Cleiton Echeveste

Gabriela Romeu – Journalist, documentary filmmaker and writer, specialized in cultural production for children, with twenty years of experience in projects that address children’s themes and developed on different platforms, such as books, documentaries, websites and exhibitions.

Leo Carnevale – Actor and clown, member of the Board of Directors of CBTIJ/ASSITEJ Brasil.

Q – First, we want to thank you for your willingness to give this interview to CBTIJ. As an entity that has a look at childhood and youth and that brings together theater professionals who work for this segment, it is a pleasure to be able to maintain this dialogue with you. We hope that this enriches our members and expands the range of information and reflections on children and young people.

Let’s talk about childhood and youth, with a special look at ECA – Statute of Children and Adolescents.

A – I appreciate the invitation to speak about an important milestone in the history of childhood in the country. I arrived at the Folha de São Paulo newspaper newsroom in the late 1990s, and since then I have been able to follow how society has been impacted by the creation of ECA.

Q – ECA is celebrating its 30th anniversary this year. Its Title I – PRELIMINARY PROVISIONS, Art. 4 says that “It is the duty of the family, the community, society in general and the government to ensure, with absolute priority, the enforcement of the rights to life, health, food, education, sport, leisure, professionalization, culture, dignity, respect, freedom and family and community coexistence”, during this time, can you observe an advance for the children’s universe, based on the regulations of the Statute regarding these “assured” rights?

A – Yes, since the 1990s, we have come a long way from the debate on children’s rights in the country. ECA emerged in the midst of the 1988 Constitution and the strong role of militancy in the area, important movements such as the National Movement of Street Boys and Girls and the emergence of several third sector institutions dedicated to the causes of childhood. Andi, for example, appeared in the period and was very important to support journalists in the newsrooms with the aim of expanding the agenda and the debate on several issues involving children and adolescents. Andi also analyzed press coverage and pointed out deficiencies, developed publications that helped improve reporters’ understanding in areas such as health and education. With ECA and all this movement that propelled it, a great circle was created to take care of children across the country.

Q – The words Culture and Education appear 11 times each in ECA in the “Titles”, “Chapters”, “Sections” and “Articles” that compose it, in an 82-page text. In your understanding, are these two segments, fundamental in the formation of human beings, well represented in ECA? Are these rights well secured?

A – To better answer this question, I would need to have a more technical reading of the Statute, and I don’t. But what I can say, as a journalist dedicated to childhood for more than two decades and having shared the reading of important experts in reading the Statute, is that it has international recognition, we have a good Statute. The discussion year after year – and especially on their “anniversaries” – was how to implement it, strengthening the entire network of actors around the child and adolescent. Despite the advances in recent years, in many segments, from the universalization of education to the fall in infant mortality rates (which alarmingly rose again…), children still suffer from the most diverse vulnerabilities and many dropouts, in different social classes. But, yes, black children and adolescents, from the peripheries, are atrocious victims of structural racism, of a country of many forms of violence and of the colonialism of the adult world in childhood. Today, with all the anti-democratic and fascist threats that we are experiencing, we have taken a step back, which is scary. What we need is to ensure that the ECA itself exists and to avoid losses and setbacks in the law itself.

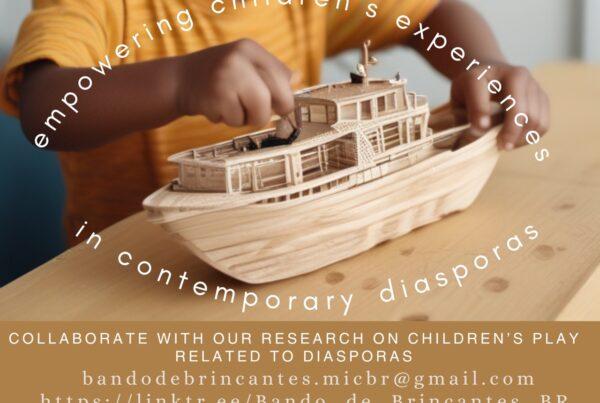

Q – The expressions Play and Have Fun only appear in ECA once each one of them in Chapter II that speaks OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM, RESPECT AND DIGNITY in Art. 15. Children and adolescents have the right to freedom, respect and dignity as human persons in the process of development and as subjects of civil, human and social rights guaranteed in the Constitution and in the laws. Being specified by Art. 16. The right to freedom comprises the following aspects: IV – playing, playing sports and having fun; with your extensive research on the world of children’s games with the creation of the award-winning “Mapa do Brincar” and the “Projeto Infâncias”, how do you see this particularity? Is this right well guaranteed, even though it is so little mentioned?

A – The right to play is under constant threat in contemporary childhoods, especially in large urban centers, where people live in tiny spaces, with fragmented daily lives, involved in technical education. I always say that the child, however, has a brilliantly transgressive spirit and plays in every time and place, because playing is his way of being, communicating and learning the world. She finds a way to play, transgresses the dryness imposed many times by the adult world. What does not take away from us adults the responsibility of ensuring legal mechanisms to guarantee this essential right to a full childhood. It is essential to guarantee the time and space for the child to play – and spontaneous, authorial and autonomous play, of course, unlike the pedagogical play that plagues many school spaces. The school, the place where children commonly meet, live and play (and that despite all the deficiencies they cover, we know), is very important for the development of culture among peers, that is, for the exchange of that children’s own knowledge. It is also worth mentioning that the current health crisis we face, among so many other evils, affects the important corporal expansion of children, who, despite not being at risk, are totally vulnerable and affected by all this confinement (necessary to save lives, it is obvious).

Q – In Art. 4 we spoke above and says that “It is the duty of the family, the community, society in general and the public authorities to ensure, with absolute priority, the realization of the rights relating to life, health, food, education, sport, leisure, professionalization, culture, dignity, respect, freedom and family and community coexistenc.”, how do you see the performance of public authorities in fulfilling and developing these “absolute priorities”? What about the other “actors” in this “community”, the “family” and the “school”?

A – We have laws that ensure children and adolescents as a subject of rights, who must receive full protection and with absolute priority. And yes, this is shared by the State, families and society. Thus, we are all constitutionally and morally responsible for all children, whether they are my children and the children of others, whether they are children who are unaware of fatherhood and motherhood. But law and reality do not go hand in hand, unfortunately. And there is a lot of ignorance about all this. According to Instituto Alana’s Absolute Priority program, 40% of the Brazilian population knows little or nothing about the rights of the child. That is, to be applied, the ECA needs to be known, disseminated, discussed …

Although ECA is completing 30 years in 2020, it is a mature statute, I feel that society often sees childhood and adolescence with “lessened” or “minored” eyes, in order to dialogue with the old Code of Minors, which dealt with abandoned, juvenile offenders, vulnerable social classes, as if other children were smaller. The child is always that other, sometimes the other who is not “my child” (s/he is the “abandoned child”), sometimes the other who has no voice and is only liable to the commanding voice of adults. It is still challenging to see the child as a subject of rights. In this context, with an ingrained conception of childhood marked by negativity (the child is defined by what s/he does not know, does not do, does not speak), it takes a lot of work for society to understand this “absolute priority”. And, maybe even before that, until we face our wound – living in a country with such a great social abyss, that is, without equity and social justice – so much more difficult will it be to discuss the priorities of childhood.

Q – In Chapter IV, which deals with THE RIGHT TO EDUCATION, CULTURE, SPORTS AND LEISURE, Articles 58 and 59 speak respectively: “In the educational process, cultural, artistic and historical values specific to the social context of children and adolescente are to be respected, guaranteeing them freedom of creation and access to cultural sources.” and “The municipalities, with support from the states and the Union, will encourage and facilitate the allocation of resources and spaces for cultural, sports and leisure programs aimed at children and youth.” What have you seen with regard to these articles, since the research you carry out spans the country?

A – I walk more in Brazil’s backyards and much less in schools. But, wherever I go and a lot from what I see, the social and cultural context of children and adolescents are often not respected, unfortunately, in the educational process. And I can say this only from my travels and from the dialogue with some realities in the country, so I just stick to it, it is worth mentioning. The singularities of childhood are not considered from the very architecture of the schools. I’ll give you an example. Imagine what it is like to live in the Pantanal region, on the banks of the Paraguay River, amid a pungent nature and the master of many knowledges. How many stimuli and learnings just in the surroundings, no? Then you arrive at the school, a box with almost no windows, stuffy, with its back to the river that has its natural air conditioning. In other words, if the school does not even speak to the place, how does it dialogue with the people and children of the place? Then we enter the classroom and pinned to the walls we see these letters and drawings of an alphabet. There we see the traditional “h” for home (a generic house…), “d” for dice, “e” for elephant… Where is Freirian (*) literacy (just to mention one of our masters) that starts from reality, the life stories of students and students?

I also realize that the school, in urban and rural areas, is still little open today to the culture of childhood. The school has a lot to learn from the backyard, a space for the full exercise of childhood. It is necessary to “backyard” the school, to consider the knowledge of the backyards exercised by the children – I spoke more of this in this text here (https://projetoinfancias.com.br/site/projetos/artigos/artigo-2/).

Q – In Chapter II, within the topic of SPECIAL PREVENTION, Section I, INFORMATION, CULTURE, LEISURE, SPORTS, FUN AND SHOWS Art. 76 says: “Radio and television stations will only show, at the recommended time for children and young people , programs with educational, artistic, cultural and informational purposes.” Do you see these criteria being met? What is your assessment of the audiovisual content made available to children and young people in Brazil?

A – In recent years, there has been an important movement to protect children from the broadcast of violent consumption on open TVs, but there has been no parallel to this defense of children’s programming in the same spaces, ensuring quality programs for children. Advertisers are gone, the schedule grid, too. The children were helpless in the face of the “open sea” program, exposed most of the time to content that needs mediation (which we know is a deficiency in Brazilian families, who still have TV as a nanny and often as the only entertainment). And, yes, it is also important to consider that the great playground of many contemporary childhoods is the internet, which allows greater diversity of content, but also requires mediation and protection strategies. Returning to television, the context, of course, is different in pay TVs (far from being a scenario without challenges), with access much more restricted socially and economically. In paid TVs, new channels emerged and programming grew, including the promotion of audiovisual via the Sectorial Fund, which propelled the increase of national quality productions aimed at children and youth audiences, many of them created after careful development. Again, it is alarming that all of this is threatened by the degrading dismantling of culture today, affected, butchered by a cultural war full of backward concepts.

Cultural productions (and here I expand to different languages, including theater, literature, cinema, music, visual arts …) build our symbolic house, constitute us as subjects, from the foundation and since childhood. And so it continues to constitute us throughout our lives. It is necessary to ensure that children have access to cultural production, the arts and the many cultural manifestations throughout Brazil.

(*) Paulo Freire (1921-1997), Brazilian educator and philosopher who was a leading advocate of critical pedagogy. He is best known for his influential work Pedagogy of the Oppressed, which is generally considered one of the foundational texts of the critical pedagogy movement. (Wikipedia)